BIRGIR ANDRÉSSON

The Closets of the Icelandic Myth

The best weapon against myth is probably to mythologize it and create a virtual myth: the new myth thus created will become a real mythology. As the myth is nurtured by the language, why not nourish on myth itself? (Roland Barthes)

One of the most important topics of twentieth century art is a constant research on the nature and function of the visual language: instead of showing us a picture of the world artists tend to show us a picture of the visual language we use to communicate with the world. They have gone through difficult questions on how the visual language can be used to create meaning and how it can lose its meaning or acquire a different one.

From the beginning Birgir Andrésson has worked in this spirit. His research has touched the relationship between visual and spoken language, and the relationship between vision and thought. Specifically exploring the social nature of visual language, how pictorial languages and forms develop to become characteristic for a certain social group or a nation. Andrésson has found his subjects in his closest surroundings; his work is based on the experience of being a participant in the Icelandic community in the late twentieth Century as well as from the exceptional experience of being born and brought up by parents who were both of them blind. From the very beginning of his life Andrésson had to deal with the complicated relationships between vision, thought and spoken language. He soon discovered on his own that vision is not limited to the eyes, but that everything we see with our eyes or in our mind is immediately transformed by thought into symbols and meanings that are subject for interpretation in the spoken language. Our definition of the meaning of visual language is to a great extent a social agreement ruled by circumstances and context that is to a great extent of a social nature.

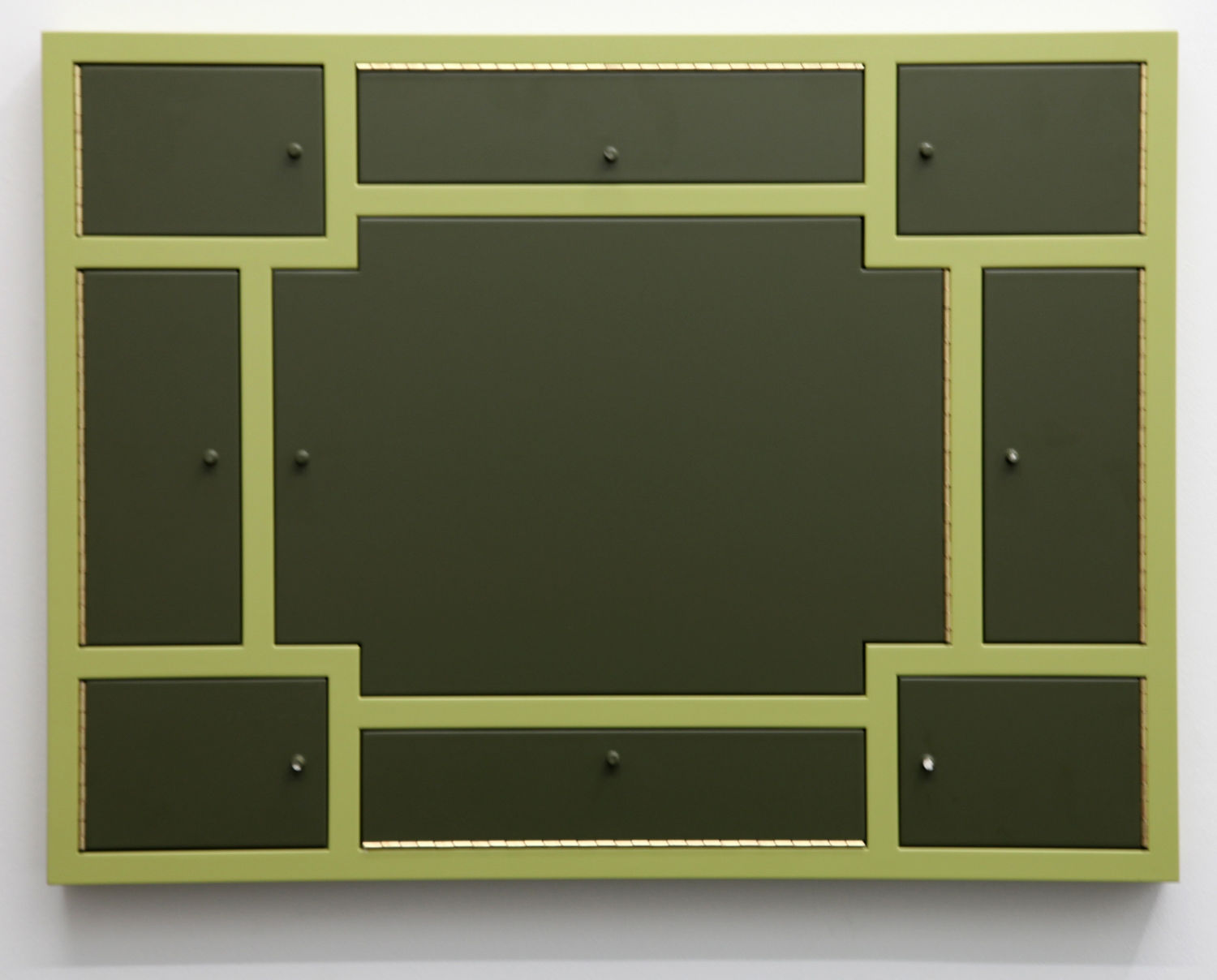

The works that Andrésson is now showing in Gallery I8 are based on stamps issued by the Icelandic Post office in the forties. They show a statue by Einar Jónsson of Thorfinnur Karlsefni, The volcanic eruption of mountain Hekla 1947, The Great Geyser and the Eiríksjökull glacier. Although these stamps are the premises for his works we do not see those images, rather we see the structure of the stamps or the formal frame where the images were inserted. Out of these frames Andrésson has built cabinets with closed boxes that have been painted in colors that he calls “Icelandic colors”, probably in order to distinguish them from “foreign” colors. This series of cabinets is parallel to another series he made several years ago on the stamps issued 1930 on the occasion of Icelandic parliament’s thousand-year anniversary. What these stamps have in common is a certain mythologization of their subjects in harmony with the Icelandic nationalism that reigned in Iceland the decades before the self-declaration of the Icelandic Republic in 1944. Einar Jónsson’s statue of the Viking-seafarer and explorer Thorfinnur Karlsefni was on show at the World Fair in New York 1939 and is still preserved somewhere in Philadelphia to commemorate the Vikings’ discovery of America. On the stamp we see this statue in a heroic vertical posture, just like the outburst of energy coming from The Great Geyser, and the volcanic eruption of Hekla is depicted on the stamp as crowned with a halo illuminating the nocturnal sky just like the bald calotte of the Eiríksjökull glacier. These images do not intend to show just the phenomena depicted; they are interpreting these phenomena in a sublime and heroic way in order to build an image of Iceland and the Icelanders in a heroic glory. They make part of that myth the Icelanders created about their country and their history in the decades before the foundation of the republic.

The Icelandic myth created by the energetic and enthusiastic generation of Icelanders that was born around year 1900 was probably as far from reality as it could be, but it served important political means. It succeeded in making the nation believe in an artificial image, and on the roots of that belief many miracles were achieved in the political field, although several of the utopias of that generation proved to be a stillbirth. For example, the dream of the eternal virginity of the feminine image that was the symbol of their fatherland.

Andrésson’s method of dismantling this myth is to empty it of its content, but use its formal structure. The stamp-image of The Great Geysir does virtually show the hot spring in all it’s might, but its purpose is not to show this phenomenon, but to transfer this explosion of energy onto the image of the country and its people. The image tells us that in this country there is an energy of almost a supernatural kind that dwells not only in the earth, but also in its people. As Roland Barthes has pointed out it is the nature of myth to empty language of its content but use its formal structure as a container for a new content that will be propagated as almost a natural law. Andrésson exploits the formal structure of this old myth by emptying it of its content literally, making closed boxes out of the different forms. By doing so he creates a myth of a second degree, a kind of artificial myth about the closed boxes of the Icelandic national character and of Icelandic visual language. The colors of the closed doors stress the meaning of this new “myth.” The “Icelandic” colors are first and foremost a matter of definition, and have as much or as little to do with reality as the myth. Actually, they are built on what Andrésson considers to be the color-taste of the generation from the turn of the last century, but that taste is as intangible as the ether and the label “Icelandic” as unreliable as the one used by the blind as well as the seeing for what passes before their eyes. The closets of Birgir Andrésson show us the Icelandic myth of the second degree as he dismantles it before our eyes.

- Ólafur Gíslason, Arthistorian and Critic