JANICE KERBEL: Cue

Janice Kerbel (b. 1969) is a London-based Canadian artist known for rigorous “studies” which are at once realizable and imaginary. Her diverse body of work includes: Bank Job (1999), a detailed master-plan to rob Coutts Bank in London; Deadstar (2006), a town map of a ghost town; Remarkable (2009), a series of typographical posters announcing the exploits of exceptional performers; Ballgame (2009-12), a scripted play-by-play commentary of “a statistically average” baseball game; and most recently Kill The Workers! (2011), a play written for theatrical lights.

Kerbel has held solo exhibitions at: Chisenhale Gallery, London; Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsrhue; Tate Britain, London; Greengrassi, London; and Moderna Museet, Stockholm; and has participated in the group exhibitions: Cactus Craze, Kunstwerke Berlin; True Romance, Kunsthalle Kiel; andBritish Art Show 6, Baltic Newcastle. Her 2006 radio play, Nick Silver Can’t Sleep, was commissioned by ArtAngel and broadcast on BBC Radio3. Upcoming 2012 exhibitions of Kerbel’s work include: Presentation House, Vancouver; Bucharest Biennial; and Kolnischer Kunstverein.

You’ve described as a common element in your work, “the question of visibility; trying to find form for things that otherwise can’t be seen.” Were Kill The Workers! and Cue particularly interesting for you in this regard, as you were working very literally with light and visibility?

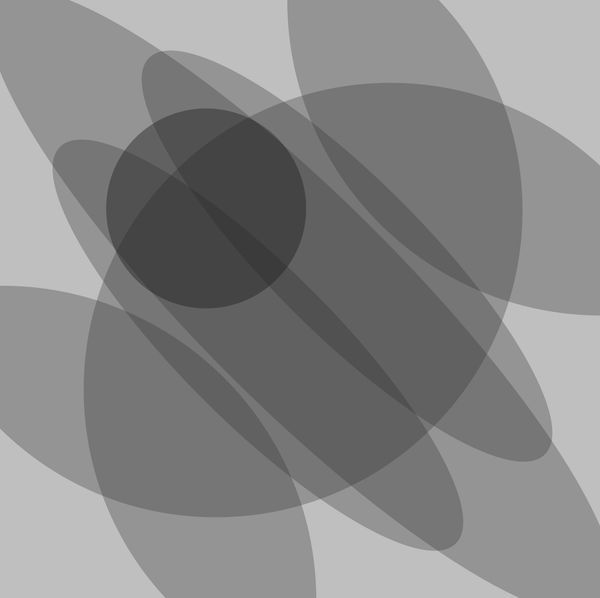

I became interested in the idea of writing a play for light in part because it is the very thing that allows for visibility in the first place. I wanted to think about the language of lighting and I wondered if there were potential narratives inherent in this language. When I was finishing Kill the Workers! I began to worry that the entire piece might be invisible, for if light has nothing to bounce off of – ie. actors, props, etc. – there might simply be nothing to see. The surprising orientation of the work onto the floor, therefore, became paramount, and made me think about the relationship between a two-dimensional plane and three-dimensional space in a new way. I wanted to take this a bit further with the prints, which are flat, but built up through the use of layered inks of varying opacities, and therefore a bit difficult to read in terms of understanding exactly how they are made and where the light is located.

Is there, then, a direct relationship between Kill the Workers! and Cue?

When I began working on Kill the Workers! I struggled to find a formal language with which to write the piece. While it began to take form as part technical cue sheet and part traditional script, there was no way for me to test out the light changes I was imagining. I began to do topographic drawings for each individual lighting state so I could imagine how the piece might look as the light hit the floor. While doing these drawings, I became aware that their construction was almost the inversion of what would happen in Kill the Workers!. This is because of the simple fact that when you increase the intensity of light everything becomes lighter, but when you increase the intensity, or opacity, of colour/ink everything becomes darker. It was this paradox that allowed me to think that the drawings could become something in their own right.

What was the line of reasoning and aesthetic/material decisions that led to the prints as they exist now?

I plotted out 36 moves, or cue changes, using 10 basic shapes and 6 grades of black. I wanted the shapes at times to refer to things in the real (ie. door, window), at times to act symbolically (ie. moonlight), and sometimes to form general cover of an 18” x 18” square. Perhaps they become the actors. While the prints maintain the language of theatrical lighting, I wanted them to be somewhat idealized, almost hypothetical in their form.

Silkscreen seemed to be the appropriate means with which to develop these works, both because of the additive dimension of the process (ink prints on top of ink to build a denser black), and for the clean geometric shapes it produces. The blacks move from the most transparent – and thereby closest to light, or white – to an almost opaque, black tone. Working with a restricted number of repeated shapes, opacities and orientations (screens can only turn 90 degrees) demanded that all changes had to occur within the conditions of a set language. I hoped this would somehow invite a sense of movement through stillness.

The arrangement of the prints suggests a story board – is there a specific narrative?

While I imagined a narrative to help me make decisions both about the sequencing and the individual workings of each print, I am pretty sure it does not translate literally to the actualization of the work. In my mind, the prints recount visibility’s desire to find form through the voice of a light (or, for light to be seen as light alone, rather than a representation of light). The prints – each a cue, or state of light – move from an imagined interior space, through an argument, a farewell, three journeys to a clearing in a wood, into dusk, a dream, moonlight, and finally a dream again, where invisibility (black) prevails. This narrative is not explicit – I hope it is somehow felt, rather than read. I wanted the whole piece to be experienced more like a composition than a narrative. If there is a natural or ‘readable’ progression in the work, perhaps it is one toward total black – or invisibility – which gets built up from all the elements and opacities toward the end of the sequence of prints.

There seems to be a certain tension between narrative and form in your work. Is the narrative purely functional — a kind of minimal scaffolding that forces the structure into a perceivable form? (ie. in Baseball you averaged the statistics to come up with the “most average” game rather than creating an exciting story for the game, and in Kill The Workers! the play only exists as it relates to light cues of actions rather than a stand alone story… )

I do see narrative as acting as a scaffold of sorts. While I often employ narrative as a means to construct a work, I am most interested in what happens when it is withheld, perhaps to see what form can be borne out of its implementation. Maybe it’s a matter of wondering what narrative looks like that has attracted me to forms such as scripts, letters, theatre, and in this case, with Cue, animation. Writing has also become more dominant in my work lately, although again it does not always figure in its expected form. This is something I would like to think about more.

You are known for your meticulous research which implies an academic rigor if not approach. What function does research play in your work?

I always feel a bit uncomfortable with the idea that research is particular to one kind of artistic practice and not another. But the act of trying to understand existing languages and structures is very much part of my working practice, and often becomes the material with which I work. The act of ‘shaping’ this material and enabling it to give form to things according to its own trajectory or logic is something I think about. It is really a process of experimenting with this material, both materially and conceptually, to allow new forms to develop.

There is an interesting paradox in your work in that although you go to great lengths to realize unseen ideas/narratives into their essential language and form, in a sense they are never realized at all but frozen in an ideal state of potentiality: the bank robbery plan, the unused/unusable marked cards, the town for ghosts, the never as yet played baseball game. Could you talk a bit about that?

My work often takes different forms, but one thing that has been consistent is an interest in forms that suggest a subsequent state. Perhaps it’s my interest in the limits of the visible that attracts me to these forms, for they are borne out of the need to give form to things that can not otherwise be seen. In earlier works, such as Bank Job and Home Fittings, I think I was looking quite literally to such forms – ie. plans, studies – as it seemed important at the time that there be a kind of potential or practical application to the things I was making. More recently, my interest seems to have evolved into a wider understanding of this sense of promise. I am still attracted to these kinds of things – letters, announcements, scripts, etc. – but I now want to be able to free them of any practical or ideological constraint, to see what happens when they are looked at in isolation from their expected use.

Janice Kerbel interviewed by Lani Yamamoto, February 2012